Written by Merel van den Berg

Read this blog on Substack.

What do Japanese blossom and stress-tracking technology have in common?

During an inspiring conference trip to Japan, I saw my research on responsible stress-tracking technology in a new light.

At the beginning of this year, I received the happy news that my first paper was accepted for the premier international conference of Human-Computer Interaction: CHI. And perhaps even better, this year the conference took place in Japan. As a teenager, I had already dreamt of the hypermodern streets of Tokyo, and now I had the opportunity to see them in real life. I thought to myself, why not seize the opportunity to extend my stay and explore Japan’s beauty?

Merel van den Berg is a PhD student at University of Twente in the Interaction Design group of prof. dr. Geke Ludden. Her research focuses on the responsible design of wearable technology for stress monitoring and interventions.

Exploring two sides of Japan

The conference was scheduled at the end of April, just after the famous blossom season. My friend and I decided to arrive 12 days before the conference and explore Tokyo, Minobu, and Kamakura before heading to Yokohama, where the conference took place. There were too many highlights to mention all, but the most captivating experience for me was renting a car and driving from enormous metropolis of Tokyo to the small Buddhist mountain village Minobu. One of the most magical experiences during this drive was the sudden appearance of Mount Fuji, a majestic natural wonder with its top covered in snow. Every now and then it would disappear, covered by other mountains or hills, leaving me longing to see it again. Minobu itself also felt like a mystic place in the middle of nature, where Buddhist monks were chanting, drums were beating, and wild monkeys were chattering. We stayed at a temple lodging where we wore traditional Japanese clothing (a yukata), enjoyed Buddhist cuisine (lots of soy beans), and improved our calligraphy skills (writing in Kanji).

Minobu contrasted with the modern and international ambience at the conference in Yokohama. Researchers from all over the world gathered to hear or share the latest insights in the field of Human-Computer Interaction. One particular presentation, by Nai-Yu Cheng, left the strongest impression on me: she explored how technology could best provide mental support to young adults in Taiwan. As current research on digital health predominantly reflects Western cultural perspectives, she investigated how we could integrate Eastern cultural viewpoints on mental wellbeing and coping strategies in digital tools for mental wellbeing support. She explained that Taiwanese young adults often employed collectivist-oriented coping strategies, such as seeking like-minded others, to enhance their sense of belonging (Cheng et al., 2025).

View on Mount Fuji, a pagoda, and cherry blossom

Are the Japanese less stressed?

I recognized this need for harmony and collectivistic wellbeing during my stay in Japan. People were respectful and extremely helpful. People on trains would stay quiet to not disturb others. When I asked directions somewhere, the people would walk with me until they were sure I would arrive at my destination. I had never felt this safe and cared for by strangers before. It made me wonder, are the Japanese less stressed? In the Western part of the world, consumer technology is increasingly used to monitor and improve health, including mental health. Fitness trackers and smartwatches are more popular in The Netherlands and United States than in Japan (Bashir, 2025). Particularly, some fitness trackers enable individuals to track their stress levels. Does the Western world have a higher need for tracking stress responses compared to the Eastern parts of the world?

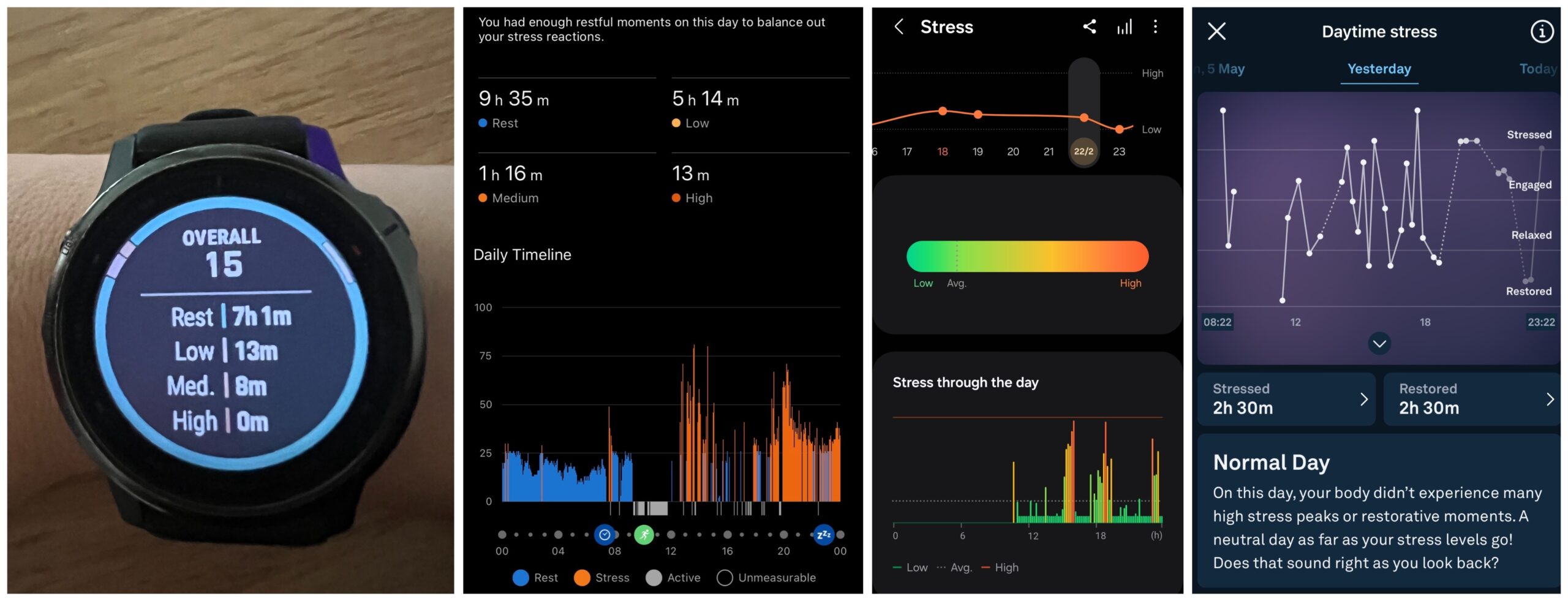

Below, there are some examples of wearable technology (smartwatches and smart rings) that show stress scores over the day. In our recent provocation paper (van den Berg et al., 2025), we take a critical stance towards these stress scores and address the shortcomings. For example, we might expect that wearables reflect mental stress, while actually, they simply measure how stressed the body is, which might also be affected by exercise, alcohol, or allergies. Another issue is that wearables always present high stress scores as bad, while being stressed can be a very healthy and positive reaction in the moment. Think about instant alertness when a fire alarm goes off, or excitement when being surprised. Therefore, the stress scores alone are currently not very informative and might give off the wrong impression. In Stress in Action, we aim to develop a better understanding of stress, how we can measure stress responses accurately, and when we might see stress levels as “good” or “bad”.

The image shows stress scores provided by three different wearables: Garmin Fenix smartwatch (1+2), Samsung Galaxy Watch (3), and Oura ring (4)

A blossom perspective

The research goals of Stress in Action also involve asking critical questions about current stress-tracking technology and how we can design responsible stress-tracking technology in the future. Just like the blossom leaves in Japan, I think it is good that we sometimes (temporarily) drop our old ideas and beliefs and take a fresh perspective on things. What does stress mean to us? Is it more important to measure it through technology, or to pay attention to the experience of stress in our bodies? Is it healthy for us to have constant access to real-time stress measurements? Should we let technology decide what stress levels are desired, and when to intervene? I look forward to exploring such questions within the Stress in Action consortium in the coming years.

Interested in more? Listen to the podcast Stress Navigation with Geke Ludden in Dutch: ‘Geke Ludden over het ontwerpen van gezondheidstechnologie en het betrekken van gebruikers’ and the podcast with Els Maeckelberghe in Dutch: ‘Els Maeckelberghe over ethiek in (stress)onderzoek en technologie’

References

Bashir, Umair (2015). Share of eHealth tracker / smart watch owners in 53 countries & territories worldwide, as of January 2025. https://www.statista.com/forecasts/1452576/share-of-ehealth-tracker-smart-watch-owners-in-selected-countries-worldwide

van den Berg, M. K. N., Karahanoğlu, A., Noordzij, M. L., Maeckelberghe, E. L. M., & Ludden, G. D. S. (2025). Why we should stress about stress scores: issues and directions for wearable stress-tracking technology. Interacting with Computers, iwaf036. https://doi.org/10.1093/iwc/iwaf036 or read more on the website.

Cheng, N. Y., Wong, N., & Reddy, M. (2025, April). Understanding Mental Wellbeing and Tools for Support with Taiwanese Emerging Adults: An Eastern Cultural Perspective. In CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI ’25), April 26–May 01, 2025, Yokohama, Japan. ACM, New York, NY, USA, 18 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3706598.3713143.